Copyright law protects the exclusive rights of creators of various works: writers, artists, musicians, etc. You can’t take someone’s painting and display it in a gallery as your own; the same goes for music and books. You can’t copy and sell these works as if they are your own works, either. However, there is a limitation to copyright law: you can buy and resell the works of others—according to the first sale doctrine.

This is exactly what millions of people do by selling used (and not used) goods—not only works of art. When we buy something, we don’t buy copyright rights for it; we just own a physical or digital object that we can rent, resell, destroy, or give away—at our own discretion.

Or can we?

Here’s an example. As a student who majors in bridge engineering, you may have probably bought The Tower and the Bridge: The New Art of Structural Engineering by David P. Billington for your collection at some point in your studies. Say, you bought it new from the bookstore. Now it’s your property—this exact physical paperback copy. |

Yet, there is a bit of a situation around the first sale doctrine regarding used books (there’s always, isn’t there?) Let’s try to decipher why it looks pretty much like the shadow library dilemma we discussed in one of our earlier posts and how it can affect everyone who’s closely related to the book industry and book resellers in the first place.

- What Is the First Sale Doctrine?

- Exceptions to the First Sale Doctrine

- The First Sale Doctrine and Goods Made Overseas—The Unhappy Publishers’ Case

- The First Sale Doctrine and Libraries—The Internet Archive Case

- How Does the First Sale Doctrine Affect the Used Book Market?

- The First Sale Doctrine Today

What Is the First Sale Doctrine?

Let’s define the first sale doctrine to get the terms straight.

In the 1908 Supreme Court case Bobbs-Merrill Co. v. Straus, the Court held, “In our view the copyright statutes, while protecting the owner of the copyright in his right to multiply and sell his production, do not create the right to impose, by notice, such as is disclosed in this case, a limitation at which the book shall be sold at retail by future purchasers, with whom there is no privity of contract.”

The Copyright Act of 1909 and the current Copyright Act of 1976 are both based on the same principle.

According to the American Library Association, “The “first sale” doctrine (17 U.S.C. § 109(a)) gives the owners of copyrighted works the rights to sell, lend, or share their copies without having to obtain permission or pay fees. The copy becomes like any piece of physical property; you’ve purchased it, you own it. You cannot make copies and sell them—the copyright owner retains those rights. But the physical book is yours.”

So, let’s take a look at another fantastic book in your collection: Guastavino Vaulting: The Art of Structural Tile. As an owner, you can sell, rent, share it with friends, burn or drown it—whatever you want. Ok, we’re joking; the book that chronicles the architectural legacy of Rafael Guastavino should be treated with utmost respect and care. So, let’s take a look at another fantastic book in your collection: Guastavino Vaulting: The Art of Structural Tile. As an owner, you can sell, rent, share it with friends, burn or drown it—whatever you want. Ok, we’re joking; the book that chronicles the architectural legacy of Rafael Guastavino should be treated with utmost respect and care. |

However, we should remember that the first sale doctrine is very narrow—you can only apply it to a specific copy. Besides, it has exceptions.

Exceptions to the First Sale Doctrine

The doctrine of first sale doesn’t empower the owner to “reproduce, adapt, publish, or perform the work without the authorization of the author.” So the exceptions do not apply to

Licensed Works

Licensed Works

You can’t apply the first sale defense to licensed goods.

Digital Transmissions

Digital Transmissions

As we’ve already mentioned, the first sale exception only applies to the copyright owner’s distribution right—not to the reproduction right. Every new digital copy is generated by the transmission, which is technically reproduction.

Important Fact: eBooks fall exactly under this category—therefore, the first sale doctrine doesn’t apply to ebooks, and libraries cannot freely lend them indefinitely after purchase—only under a license and only during a set period of time.

Certain Types of Displays

Certain Types of Displays

Only copies publicly displayed directly or one image at a time can be covered by the first sale exception.

Unauthorized Copies

Unauthorized Copies

Only “lawfully made” copies can be protected by the first sale doctrine. It can’t be applied to the distributions or displays of illegally made copies.

Now that we’ve defined the first sale doctrine and specified its exceptions let’s try to understand why there’s controversy around books and the first sale doctrine application and take a look at the two most prominent cases.

The First Sale Doctrine and Goods Made Overseas—The Unhappy Publishers’ Case

The first case can be related to the last exception we mentioned earlier—unauthorized copies.

It’s not news that American textbook publishers create identical or very similar international textbook editions and editions that are intended for sale overseas at lower prices. While these editions are not unauthorized copies, there’s a similarity in how publishers react to the first doctrine application in their case. Here is an example.

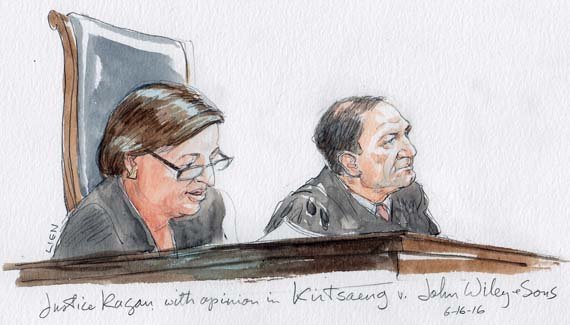

In the Kirtsaeng v. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. case in 2008, Wiley & Sons sued Kirtsaeng (a Thai student living in the United States) for copyright infringement. Kirtsaeng’s family in Thailand helped him purchase and ship to the US about 600 textbooks published by Wiley Asia (John Wiley & Sons’ foreign subsidiary.)

Wiley Sons alleged that the company had never given permission to import books to the United States, and the notice on them contained an explicit prohibition as well as a label for exclusive distribution in Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, “This book is authorized for sale in Europe, Asia, Africa and the Middle East only [and] may not be exported. Exportation from or importation of this book to another region without the Publisher’s authorization is illegal and is a violation of the Publisher’s rights. The Publisher may take legal action to enforce its rights. The Publisher may recover damages and costs, including but not limited to lost profits and attorney’s fees, in the event legal action is required.”

Kirtsaeng used the first sale doctrine to defend himself in court. He stated that he didn’t need the publisher’s permission to resell the books in the United States. The federal district court sided with Wiley & Sons, and so did the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit: the first sale doctrine can’t be applied to works produced abroad.

However, in 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the decision and ruled that there’re no geographic limits on the first sale doctrine—physical books produced and purchased abroad could be imported into the U.S. for reselling purposes—there’s no violation of the copyright owner’s distribution rights under copyright law.

The case caused a stir. The publishers weren’t happy.

To sum it up, now you know that if you happen to buy a copy of Shell Structures for Architecture: Form Finding and Optimization published by Routledge—which is a British multinational publisher—you can bring it to the U.S. and sell it any time on a second-hand market without any worries or concerns. It’s absolutely legal. To sum it up, now you know that if you happen to buy a copy of Shell Structures for Architecture: Form Finding and Optimization published by Routledge—which is a British multinational publisher—you can bring it to the U.S. and sell it any time on a second-hand market without any worries or concerns. It’s absolutely legal. |

The First Sale Doctrine and Libraries—The Internet Archive Case

The first sale doctrine copyright application has always been important for libraries. It’s the basis that allows them to lend books to the public. And while there’s always been some tension between publishers and libraries, in the case of physical books, things are crystal clear: libraries purchase books they lend to patrons—in this situation, the first sale doctrine is 100% applicable.

However, in our digital world, things got complicated. You can’t apply the doctrine’s digital transmissions exception here, as the process for lending eBooks is different. As we’ve already mentioned earlier, libraries rent eBooks from publishers under a paid license. Therefore, they can only lend an eBook a certain number of times; then, the license needs to be renewed. Licenses are expensive, and not every library can afford them.

In this respect, the Hachette Book Group et al. v. Internet Archive case is interesting. In 2020, the Internet Archive—which offers scanned books available to the public for free via their website—was sued for copyright infringement by the four publishers: Hachette Book Group, Harper Collins Publishers, John Wiley & Sons, and Penguin Random House. They accused Internet Archive of copyright infringement and violation of their exclusive reproduction and distribution rights under the Copyright Act of the U.S.

According to the publisher, the first sale doctrine does not apply to the unauthorized reproduction of a work (which they accuse the Internet Archive of doing). The Internet Archive insists that they stick to the best practices of controlled digital lending, where they buy (they become owners), scan copies of these books (as allowed by the first doctrine) and lend them online to patrons one at a time (pretty much like physical books in physical libraries are lent) for free.

But for publishers, scanning books to make digital copies is an act of reproduction, not distribution, which makes the first sale doctrine immediately redundant and impossible to be used as a defense in court, which also means that Internet Archive is breaking the law.

On the other hand, for those who advocate for open access to books and study materials, the case illustrates how anxious publishers are about losing a share of the eBook market and their profits from expensive licensing agreements.

While the case isn’t ruled out when we’re writing this article—the lawsuit has been ongoing for over two years now and will probably take years to resolve—we can only wait and see the outcome.

So if bridge engineering is your major and electronic music is your hobby, you may have already read Techno Rebels: The Renegades of Electronic Funk—this comprehensive study about Detroit Techno, its origins and impact. If you haven’t and are of two minds about renting it from the Internet Archive, you should probably do it now, as there’s a chance you won’t be able to use this option in the nearest future. So if bridge engineering is your major and electronic music is your hobby, you may have already read Techno Rebels: The Renegades of Electronic Funk—this comprehensive study about Detroit Techno, its origins and impact. If you haven’t and are of two minds about renting it from the Internet Archive, you should probably do it now, as there’s a chance you won’t be able to use this option in the nearest future. |

How Does the First Sale Doctrine Affect the Used Book Market?

So what’s the current situation?

On the one hand, there’s the copyright first sale doctrine that allows a fair share of activity in the book world—from garage sales to libraries and used bookstores—with plenty of organizations and companies (e.g., the American Library Association, the American Association of Law Libraries, Goodwill, Powell’s Books, eBay, etc.) using it to support their activity. There are also plenty of online used booksellers that can actually function as a business solely due to the existence of this doctrine.

On the other, there are publishers and their annoyance regarding the profits they lose due to the entire used book reselling business (and the entire digital book business they are hysterically trying to control). Textbook publishers are understandably vexed (more than others) by the first sale doctrine copyright application, and they’re constantly trying to interfere with any business or organization that eases access to textbooks and study materials (remember shadow libraries?)

In other words, the first sale doctrine protects used booksellers (as well as a million other retail businesses). Without it, you’d be unauthorized to donate books to charities and libraries, libraries won’t be able to lend books, and book businesses and book buyers would be cut off from a fair share of affordable books (again, a million other retail businesses and users—from jewelry to used cars—would suffer according to the same scenario).

That would be the world where your act of selling a copy of Beyond Bending: Reimagining Compression Shells to a used bookseller (or even giving it away to your fellow student) would be considered a copyright violation. The thing is that while the representatives of other industries—say, automotive—don’t see it as a problem (it’s hard to imagine Chevrolet interfering with your selling your dear old Chevy to a local used car dealer), book publishers are pushing right into this direction. Not nice, right? That would be the world where your act of selling a copy of Beyond Bending: Reimagining Compression Shells to a used bookseller (or even giving it away to your fellow student) would be considered a copyright violation. The thing is that while the representatives of other industries—say, automotive—don’t see it as a problem (it’s hard to imagine Chevrolet interfering with your selling your dear old Chevy to a local used car dealer), book publishers are pushing right into this direction. Not nice, right? |

The First Sale Doctrine Today

We should take into consideration that the first sale doctrine was enacted at the time when books were accessible only in psychical formats, and it was hard to reproduce them in large quantities manually (or even industrially); there weren’t any digital books on the agenda let alone the problem of their ownership and sharing. Yet, things are changing fast.

There’s little surprise in publishers’ attempt to interfere with the first sale doctrine, as it was not convenient for them in the first place and hasn’t done them any favors ever since. They’re doing everything in their power to prevent potential profit loss in the digital market and counter the reselling business. They are backed up by software companies that also try to outsmart the first sale doctrine by introducing licensing.

One thing is clear: the first sale doctrine is no longer an ace in any copyright dispute; there’re many factors—with the advent and flourishing of digital technologies—that need to be taken into consideration regarding what practices can be considered fair use or not (not only regarding controlled digital lending). There’s a definite necessity for a better definition (and regulation) of how works created by authors and produced by publishers can be shared. At BookScouter, we advocate for more open access; however, as we’ve already said, we can only wait and see.